...are doomed to repeat it. What we call the Vietnam war, the Vietnamese call the American war; and the name of the actual village in which almost all its inhabitants were slaughtered in the My Lai massacre is not, in fact, named My Lai.

After the inevitable Why Vietnam? the next most common question people asked me was ‘Are you excited about going (to Vietnam)?’ to which I'd dutifully (and truthfully) answer yes. But this was only one component of a complex set of feelings.

I gather Americans were involved in the creation of this memorial—perhaps the reason for an American wildflower, tickseed (coreopsis)?

Mixed in with the excitement was dread, that the people would resent an American visiting their country. (In fact, as the guidebooks and the tour itself promised, the Vietnamese are astonishingly friendly; even the adults waved and yelled hello as those funny-looking Westerners wearing weird clothes, odd equipment (e.g. mirrors & bike helmets) riding odd, multi-geared freight-framed bikes rode by. But more about that on another page.)

Even more than dread, was shame.

My visit to Vietnam is the first time I've ever been off the North American continent, and in the beginning of April, when I left, never in my life had I been less proud to be American for it seemed at that time nothing and nobody could or would do anything useful to stop the invasion of Iraq. I was a child during the undeclared war that took my uncle's life; war to me meant staying in the backyard of our little house as tanks rolled down Woodward avenue during the 1967 riots. I remember the night of the first Gulf war: my principal feelings were relief, that it wasn't going to be an endless conflict like Vietnam. Too bad about all those Iraqi civilians, of course.

But at least we had some backing from the international community.

The tour guide for Son My (my little brochure doesn't really explore the fine semantic distinctions as to why this little village has two names, but I was given to understand My Lai was <em>not</em> its name) was very much moved—almost to tears, in fact—at so many “Americans†visiting this memorial. There were 22 of us including the tour guide, but I felt compelled to point out that many of the group were Australians—in fact a lot of them were New Zealanders, but never mind...

Vietnam is 12 hours ahead of Eastern Standard time, so as people here were preparing for a lighthearted celebration involving lots of cheap green beer—and I was no doubt anticipating what gifts my 7th birthday would bring—US army helicopters were descending upon this little village (it's hard for me to really get across the tiny size of traditional farming communities—that's why you keep seeing that word, ‘little’). As my mom pointed out to me in the memorial, the villagers probably <em>were</em> Viet Cong supporters, and the US army was no doubt very frustrated with the counter-attacks of the “peaceful simple-minded peasantsâ€. —I saw some of the ingenious traps used in the Cu Chi tunnels, and the variations involving nasty spikes were nearly endless.

But, hello, this was <em>their</em> country; and quite apart from the fact there are rules about slaughtering civilians (even if they turn into combatants that night), there are some moral imperatives here. Not all of the US soldiers participated in My Lai—one shot himself in the foot; another helicopter pilot swept up a few people out of harm's way, and very nearly fired upon fellow troops. No American higher-ups were ever prosecuted. (Hmm. Remind you of anything going on right now?) The fact remains, however, that this is a particularly ugly moment in American history, and a grief-filled one for the Vietnamese.

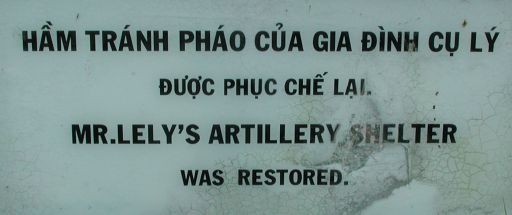

They've created a memorial, with scraps—letters, a child's primer, a spoon, a copper pot and a list of 504 names—all that remains, except the peaceful, flower filled field—one of the members of our group compared it to battlefields, like Gettysburg, which I've also visited. The infamous ditch William Calley herded over a hundred people which he then mowed down is a rather pretty block lined thing, some 4–5’ deep, evidently the town's water supply once upon a time. Oh, there's an ugly socialistic cement sculpture done in the russian style, but I found this recreated shelter a far more moving tribute.

As the guide earnestly explained the purpose of the memorial: “so this will never happen again†I thought, ‘nice try, lady. And how many Iraqi civilians have died? —I note, those numbers have not exactly been publicized by our dear government. Pray god, or goddess, or whatever force for good you recognize in the universe that we are not committing these sort of atrocities against women and children there, even as you plead for peace.’

I returned home just as the Abu Ghraib prison scandal was breaking; it was pretty much a given by the tour group, however little we might like the prospect, that Bush would be re-elected. The first thought that came into my head was, ‘oh good, will <em>this</em> be enough to shift the shrub out of office? Probably not, sigh....’

Appalling as these abuses are, they only make me ashamed to be American. In a weird way, they pleased me, because now it meant, <em>finally</em>, that some of the inevitable uglinesses that I <em>knew</em> were consequent of any war were coming out, and maybe more than just a few peaceniks would start asking serious questions about this idiotic invasion. However, when I heard about the beheading of Nicholas Berg, not even the foulest language I know could express my feelings. (And, though I may present what to some people are unpleasant ideas, I do try to keep the language on this site family-friendly.) The men who committed this atrocity claimed to be retrieving the “honor†of the abused Iraqi prisoners; instead they have disgraced the entire human race.

That is my condemnation: their acts make me ashamed not merely to be American, but to be human. Nice going, guys.

The most compelling argument against capital punishment (before all the stories about innocents wrongly convicted came out) I ever saw was in a film, proving that the arts are not merely for entertainment: capital punishment is wrong because it lowers us, the accusers, to the level of the level of the criminals we seek to punish. Thus, it doesn't matter whether the villagers aided the viet cong (if indeed they did; or worked with the Americans when they were in charge; or most likely, adapted, as the folk with no guns, to whatever those with weapons forced them to do); or whether the Iraqi prisoners were presumably murderers and rapists (as one US congressman pointed out); or what the dickens Nicholas Berg was doing in Iraq (I don't buy the story they're telling on the news—much as I feel for his parents’ grief I cannot imagine anyone going there in hopes of getting a contract to repair the infrastructure—there's some major pieces of the story missing here). Killing and torturing these people was wrong, a crime against humanity.

Slaughtering the villagers of Tinh Khe was wrong. Abusing and murdering prisoners in Abu Ghraib was wrong. Beheading Nicholas Berg was wrong. In all three cases, it seemed to me that people (well, men, if you want my honest opinion) took a great deal too much pleasure in the pain and suffering of others, and to all the perpetrators of such cruelty, I say, shame. Perhaps our tour guide's hope—that we never forget—is truly a vain one. But...

Never forget.

Unless otherwise noted, text, image and objects depicted therein copyright 1996--present sylvus tarn.

Sylvus Tarn