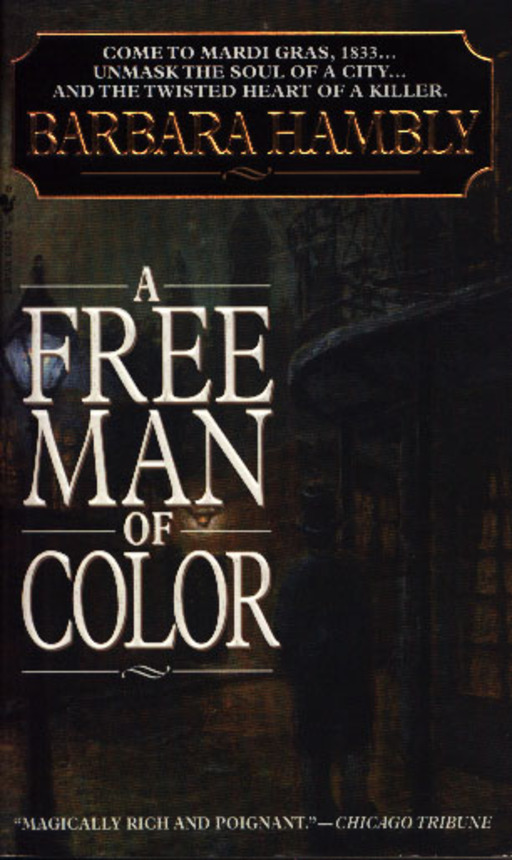

Bantam Books, 1997, 412 pp.

I believe that sometimes, when jumping from one genre to another, authors switch nom de plumes, in order not to set up unreasonable expectations amonst their established readership. However, I freely admit that I purchased this book because I had enjoyed Ms. Hambley's excellent fantasy, and was awfully glad she used her own name, because otherwise I probably would've missed this superb historical mystery.

Hambly chose her period carefully—New Orleans in the 1830s, as the the English speaking Southerners’ less refined customs are creating rip tides in the more sophisticated French-American culture of the Quarter. Chief amongst these is placage, the contractually bound taking of part black mistresses by wealthy Orleaners.

Though slowly being whittled away, blacks have considerably more freedom in New Orleans than elsewhere in the south; nevertheless, Benjamen January, the child of three black grandparents and a former slave—freed when his mother was purchased and manumitted, nevertheless had emigrated to France from his mother and his more highly valued half sister of three white grandparents upon adulthood.

But when grief propels the professional pianist back to his home at the beginning of the novel, playing at the balls where the white men and black women consort, he quickly becomes embroiled in a murder of the town's most extravagant and cruel courtesan, Angelique Crozat. It does no good to state that I didn't have a clue who the murderer was till the end, since even a halfway competent mystery writer can fool me, but I did find the shifting suspects—among them January himself—and motives to be intricate and well thought out. And yes, the clues were dutifully laid down for those who can catch these things.

Besides the rich characterizations, especially of January's family, whose relationships, like those of the society they live in, are filled with many and conflicting currents, the extraordinary atmosphere provides a stunning backdrop. New Orleans is noted for its colorful history and customs, and Hambly obviously did a great deal of research, which she incorporated with extraordinary skill in the novel.

This country's quest to come to terms with its heritage of slavery has been slow, and gradual, but it seems that especially in the last ten years or so there has been greater willingness to expose—and accept—the past as it really was. Hambly states that her goal was to write a good story, and she has—an excellent one, in fact. But the book represents, to me at least, that growing willingness to look unflinchingly at the past. Good as the story is, that verite perhaps may be this novel's most enduring strength. Three stars.

Unless otherwise noted, text, image and objects depicted therein copyright 1996--present sylvus tarn.

Sylvus Tarn