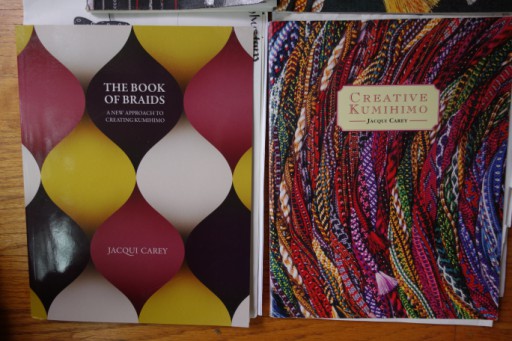

So today I thought I'd review Jacqui Carey's latest, The Book of Braids: A new approach to creative kumihimo. I actually bought this thing along with two of Makiko Tada's volumes in her Treatises of Braids series (I & VI —marudai and the first disk and plate, respectively) as prep for the 3 day seminar I took with her earlier this year. Someday, I'll do a little better job of documenting what I learned in Tada-sensai's masterclass but in the meantime here are my thoughts on a book I never even knew existed until I spotted it in Japan, in Tada-sensai's possession:) —I loved Jacqui Carey's Creative Kumihimo (and have reproduced the text of my reviews from an earlier page below, [1] and this book is another winner, but alas, I'm afraid it won't get the attention it deserves.

The main reason, I'm guessing, is that it's self-published,[2] but that butt-ugly cover sure don't help. It's not that I don't like the concept (the interlocked pointed ovals are, I finally realized, meant to be a representation of kumi stitches) and yes, I suppose it's boring that absolutely every kumi book has (duh) pictures of kumi on the cover, but for goodness’ sake, covers are advertisement. Clearly a lot of time and effort went into the writing, design and photography of this volume—why not the cover as well? If not a picture of kumi, diagrams of the new notation, traditional charting could have been very effectively combined with a closeup in neutral colors to emphasize the theoreticality of the book; also the title and author's name should've been bigger, since IME the kind of people with $50 to spend on a specialist book of this type tend to be middle-aged to old, and appreciate this sort of thing. If I hadn't flipped through this (or known Carey's rep from her earlier books) it would still be on the list of ‘buy some day, when I have a pile of cash lying around.’

That's a shame, because, once again, for the intermediate or advanced braider, it's first rate; and even a beginner with a strong textile background could probably get by. That said, the book doesn't cover the basics Carey (and others) have thoroughly documented in other, readily available books. Her goal in this volume is to give the (experienced enough) braider a conceptual framework for design.

It's had to believe it's been twenty years since she published Creative Kumihimo, and the subtleties of her distorted braids, one of which I apostrophized as ‘diseased looking’ have improved. So, I imagine, have my horizons. In a nutshell, the book aims to break down the basic movements around the marudai, which Carey divides into 4 (or 8) basic categories, which she combines with an algorithmically based notational system. She's very clear, but the non-mathematically inclined (that would be me) will probably have to attempt following the diagrams multiple times, before they sink in.

Fortunately, the concepts are lavishly illustrated throughout, and the various aspects that affect braids beautifully illustrated in a wonderful series in the opening chapter documenting

- braid structure (naturally)

- fiber – whether soft, firm, twisted, unspun

- thickness in thread gauge (i.e. mixing thick and thin yarns)

- number of ends per tama (another way of mixing thick and thin)

- plus of course color.

Then she moves on to her new notational system, breaks down the moves, discusses how to expand the number of tama (which was indeed covered in Creative Kumihimo but here she includes a lot of asymmetrical tama groupings, going into quite a lot more depth for us unimaginative types). “Mixing Actions” delves into the seemingly obvious, but critically important need to keep groups of tama balanced through the sequence, and which categories of (mixed) moves are more likely to work well. This is the meat of the book, what distinguishes it from one with merely a number of fun braids to make. The next chapter goes into depth on mixing fiber types—opening with an amusing pic of braided edible(!) spaghetti. The next chapter discusses how the braider can adjust hir technique, and then we have a gallery, um, how to use braids. Besides a stunning Japapese carved and lacquered box, there's also several views of her famous kumihimo appliqued jacket, including some closeups, as well as some playful examples, such as the in-progress photo of led tubing, or the cushion requiring a truly giant marudai.

The book's final main chapter concludes with some concrete examples of some 24 sequences, diagrammed with her new notation and explanatory text, each with 4 (usually quite different) samples of each. Photographs, full-size or perhaps even enlarged, of the samples are shown directly below the starting diagram, showing tama and color arrangement, much nicer than having to flip back and forth as in Creative. Full page gallery shots, clearly labelled, make very nice and decorative additions, allowing the reader to see more complete versions of some of the braids.

There's also a three page note for translating braids to those popular foam disks. Frankly, I didn't find it terribly helpful, as the first braid shown is the ever popular kongoh, which pretty much every-one learns first thing on a disk, as adjusting is actually easier on the disk than the marudai. Unfortunately, though the overlain N/S notation on the second set of photos on p. 119 (explaining that you can rotate the disk in your hands to make the sequence easier) is correct, the photos themselves are wrong![3] Carey goes on to explain that some sequences require a lot of futzing around (i.e. repositioning threads) and so chooses one of the most unsuitable structures for her second example. If you want to learn to use the disk to your advantage, you're better off spending your $50 (yeah, this book is $49.95 in the US) on the Tada book(s) instead. Unlike Carey, Tada (who invented them after all) has actively pursued their advantages, and yes, there are some fun things you do on a disk that would be difficult or impossible on traditional equipment.

Aside from the cover, the book is handsomely designed, thoughtfully laid out,[4] the photography good[5] the copy-editing very good, and the color reproduction and registration excellent.

This is neither a cheap nor readily available book, being roughly 2x the cost a typical manual of this type, and available, so far as I know, only from Braiders’ Hand in the US (and from Carey herself in the UK, of course.) However, for those who enjoyed her diagrams in the earlier book, or have a desire to learn more about the underlying structure of ‘oblique interlacing’, (especially to create one's own braid structures), the book is recommended.

Though I have to admit, I still wish she'd publish instructions for creating those cool stitch diagrams!

Below I reproduce reviews of other kumi books (excepting 200 Braids); these are exactly the same as the late 90s originals, excepting now being on page with tags, indexing and the like[7]

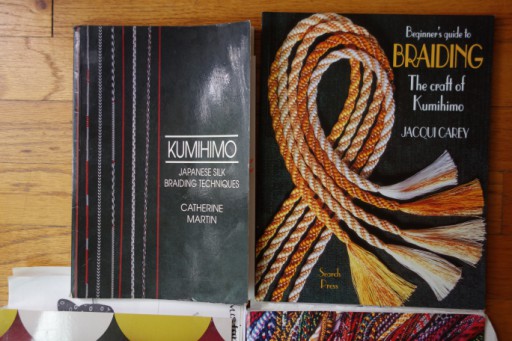

KUMIHIMO: Japanese Silk Braiding Techniques, by Catherine Martin

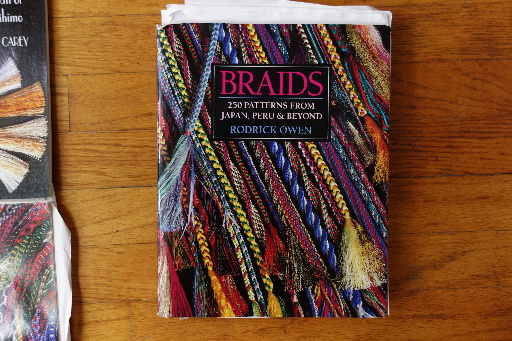

BRAIDS: 250 Patterns from Japan, Peru & Beyond, by Rodrick Owen

© 1986, ISBN 0-937274-59-3 Lark Books, 93 pp., softbound, $14.95, and © 1995, ISBN 1-883010-06-3 Interweave Press, 159 pp., $24.95

It sometimes takes me awhile to get going on reviews. When I started reviewing Braids the first time, I discovered I was discussing Kumihimo as much or more, and so decided to do two for the price of one. There is no doubt that Catherine Martin's text is the classic on this subject, at least in English, and I was positively thrilled when I discovered it: I used to make three strand braids from strips of torn sheets my exasperated Mother could not understand why I wished to preserve rather than simply undo and rebraid again. In that sense I perhaps do not have the proper Asian spirit of braiding, seen as a form of meditation by its serious practitioners. But the subject has fascinated me for years, and like the beadwork into which I incorporate most of my braids I simply lacked the knowledge to pursue the craft.

Martin's book changed all that. Following her occasionally obscure instructions, I managed, for my first effort, to rig a marudai out a soldering platform and the bobbins from stacks of chinese coins with holes in them. It didn't work very well, but I was delighted, and then began the frustrating search for a real marudai, and real bobbins. Eventually I found those too, and have been making braids in an erratic fashion ever since.

Martin, trained solely in Japan, is a traditional practitioner of the craft, not only braiding her silk in centuries old tradition, but dying it as well. She begins her slim volume with an introduction and history, and continues with equipment, materials and basic techniques. The middle section of the book details the patterns of 12 braids, starting with 4 stranders and going up to 16 strand braids, for which she gives both the Japanese names and approximate english translations. Each braid is illustrated with a diagram, a drawing showing what the braid looks like from a top-down view, and a color photograph of the finished product, printed in what appears to be roughly life size.

The culture in which artist received her training is evident everywhere: in the subtlety of the vegetable colors used to dye the silk, in the understated layout, and attractively presented braids, the photographs of which appear at intervals as in old-fashioned books, and even the calligraphy which begins this small volume. At the same time Martin is sensible of the Western mind-set, and incorporates among elaborate instructions for tying a bobbin advice such as “attach... in any way that will tie them together...” (p. 33) which I find refreshing and singularly encouraging. It's nice to know that even the experts sometimes have to jury-rig sometimes.

In addition to the twelve basic braids the author undertakes to educate the reader on how to separate bulk, unwoven silk (called flat silk by Japanese embroiderers) in groups (winding) and attaching this stuff to the bobbins (warping). Though interesting it is perhaps not germane to any but the most authentic braiders, as most fibres available in this country are twisted already into threads. Some of the other instructions, though carefully described, were difficult to follow, such as making the knot to attach the bobbin leader to the warp threads—though I've tried many times, I still doubt I've really got it right. Other information, such as the relative height of the marudai to braider, or how the bobbins should be positioned in the hands when braiding, is vague or unavailable. Nevertheless, the book is certainly enough to get anyone with the interest and a little willingness to experiment started.

Precisely the answers to questions such as how to hold the bobbins are what led me to purchase Owen's book, which just came out earlier this year. Like Martin, Owen roughly divides his book into three sections, a short one on History, followed by Equipment, Materials, and Methods, and concluding with the patterns for the braids themselves.

There are a remarkable number of similarities between the two, and I have no doubt Owen's book was influenced by the earlier work, which he lists in the bibliography of Braids. They're even printed in the same country, Hong Kong, which accounts for the reasonableness of cost and excellent sharpness and registration of the photography. Owen, though trained in Japan also, seems to have learned braiding principly, or at least first, in Peru, where it also a highly regarded form, particularly to make slings. Owen's discovery that braids have evolved independently in at least three different places—Peru, Japan, and West Africa—result in a less insular approach. Peruvians—and the Africans as well, make the braids with “nimble fingers and toes”(p. 32) but Owen adopts a fellow teacher's technique of using a slotted card, an inexpensive method which doesn't require weighted bobbins. He also details how to make a cheap marudai and bobbins, using cardboard and 35mm film canisters. For those desiring the best of both worlds, he also provides plans for a slotted board with dowel rod bobbins, which combines some advantages of the card and marudai methods.

Though technically the book does indeed list 250 different patterns, instructions for only 56 different braids are shown; however, many variations are given for each. Though it is impossible to tell exactly, my guess is that the samples have been enlarged approximately double. This makes it somewhat difficult to compare them directly to Martin's, which if anything are shown smaller than life size. Nevertheless it clear, that, despite similar training, the two have vastly different aethestics. Martin's braids are smooth, restrained as to color, with untidy ends out of sight, as the pictures of each run off the page, giving the illusion of infinite, perfect cords, whereas Owen freely uses synthetics, brilliant color and varying quantities of threads amongst the bobbins to achieve a puffy or bumpy look to many of his braids. Since he used students to test the instructions and their samples are (I assume) included, this would account for the slight uneveness of technique in some of the pictures, whereas Martin notes she made all the braids illustrated in her book herself.

The assumption that seems to be prevalent amongst so many traditional practitioners of Japanese disciplines is that any other approach cannot possibly be as worthwhile has been my major gripe with arts Japanese. Nevertheless, I admit a sneaking preference to Martin's quiet, elegant pieces, and even her understated approach. That said, there's no denying that there's vastly more information in Owen's book—not only about Japanese techniques, but two alternatives as well. For those who do not wish to immediately invest $150–200 in equipment, this is a godsend. Moreover, there are all sorts of variations concerning methods for finishing braids with tassels, pompoms and the like that can't fail to intrigue anyone interested in the subject of cords. Interestingly enough, though, some of the effects in Martin's books aren't duplicated in Owen's book: you'll either have to get both, or, as both authors strongly urge, explore, and keep good records. Like the hero escaping the minotaur, a sense of adventure is not enough. One has to be organized as well, leaving behind samples and notes of one's previous attempts, or attempting to recreate or even devise variations on an old braid will be as fruitless as retracing the maze without the tell tale string Hercules used to escape.

Beginner's Guide to Kumihimo:

Jacqui Carey

CREATIVE KUMIHIMO

© 1997, ISBN 0-85532-828-2 Search Press, 64 pp., softbound, $15.95, and © 1995, ISBN 0-9523225-0-1 Devonshire Press Ltd, 100 pp., $29.95

April Fool's Day, 1998—It always helps to know the prejudices, or at least the background, of any reviewer. They can vary considerably; mine have changed since I wrote the review above, 2–3 years ago. I got interested in braiding as a lightweight, handmade, adjustable closure for my beaded necklaces; and I still favor thin, single strand (per bobbin) cords. In other words, I'm coming out of a metalworking, rather than a weaving, background, so I don't have the experience with warping (and tangling) that weavers perforce must acquire early on.

Traditionally, however, kumihimo is braided with multiple threads, or “ends”, and its most popular use in Japan, for obi ties, yields braids about 3/8” (1cm) thick. So, I've learned that both Martin's and Owen braids are likely shown smaller than life size; that commercially available kumi silk, unlike that for traditional Japanese embroidery, is fine strands, but twisted nevertheless; and that most braiders do indeed use these multiple threads, and therefore find the dividing of warps of particular interest after all.

But I still look at book production values, because I find it hard to purchase a really badly made book and I still ignore how well or poorly the author makes suggestions for using the braids (they all seem to be about the same: ie not to my taste) Frankly, if you're asking the question, kumihimo, being so time consuming, is probably not the craft for you anyway. I've never worried how I was going to “use” my tassels, embroidery, braids, beadwork or anything else. I make it for the joy of it, and figure out what to do with it later. Eventually, I come up with something, if I don't sweat it too much.

Since I started teaching kumihimo I've become considerably more interested in its traditions, hereto only a point of academic interest. Carey's books are the latest widely available on kumihimo—the Beginner's Guide was published only last year. Frankly I bought this book primarily for the purpose of reviewing it, as it is an extremely basic text, and I've passed that stage now (I hope). For those unable to get to a teacher and wary of learning out of books, this one is your best bet.

Following a one page introduction, it covers, with a series of color photographs, how to wind threads, tie them onto the bobbins (the traditional knot, mentioned above, can be tricky for beginners, and even not so beginners) and how to make the adjustable slip knot for keeping the bobbins at an even distance from the marudai top. How to attach the counterweight bag, how to tie off (and how to cut evenly) the ends—all is shown in complete, photographic sequences.

It shows only six braids, all of them 8 stranders, but it shows a photograph at each stage of the sequence, illustrating the thread and hand positions, plus closeups, again for each stage of the sequence. She discusses hand movements, down to which fingers are used. In addition the author, a clearly experienced teacher, gives a little mnemonic to help remember the bobbin movements for each braid. The examples of each are exhaustively specified: number and color of threads for each bobbin, bobbin weight and counterweight amounts. Carey also gives multiple variations for the braids, and explores, at the end of the book, substituting fancy ribbons, such as soutache, to jazz up the braids.

The author shows a traditional marudai, a clear colorless lucite model she's developed (and sells, with acrylic bobbins) and a homemade version using a lampshade. This little manual doesn't show, let alone give any instructions, for a cardboard version, so you're on your own there. Aside from this omission, the book accomplishes its goal of a basic introduction to kumihimo with near perfection.

Excepting the cover, which with its rust, yellow and brown color scheme, and choice of font (thankfully abandoned by the title page), sent 70s kitschy-crafty shivers down my spine, the book is attractively designed. The photography of the working sequences, as well as the diagrams, is sharp; some of the pictures of finished braids are slightly fuzzy, but that's quibbling. Perhaps Carey was as unhappy with the copyediting of her previous book as I was, because with the switch in publishers, the number of fonts were reduced to one family and the book is free of the really bad copyediting problems that plagued her previous volume, Creative Kumihimo.

Nevertheless, if I could only own one book out of the four, that would be my choice (at least for now....) The book gives adequate instructions in clear, sharp, diagrammatic drawings for warping, tying on bobbins, and dressing the marudai for all but the really instructionally challanged. The main section of the book gives algorithms for approximately 42 different braid structures, each with a diagram of its cross-section, a stylized drawing, a sharp black and white photograph at the beginning point of braiding, and a pattern of the stitches, laid out flat. Besides making the relationships between the braids very much clearer and illustrating their structure in a visual manner, the patterns are ideal for those wishing to design the color scheme in advance, on paper. In both books, Carey colors in the bobbin (indicated by a circle) to be moved, making it stand out visually, a nice touch.

I admit to having bought the book in hopes that Carey would elucidate how she goes about developing these flat diagrams of braids—ever since I wanted to make the “twisted diamond” pattern for Keiruko no himo, and went about discovering it by making a very rough and ready diagram of the braid's stitches, I've wanted to get a better understanding of mathematics underlying kumihimo. I suspect I need to investigate some mathematics journals, not consult how-to books.

There is a wealth of other material, however. The book gives two methods for increasing bobbins (say you have an eight-strand braid and want to make a 16 or 24 strand version), four methods for looped ends, two methods for blunt ends, plus of course the traditional tasseled end. It shows how to finish with a Chinese ball knot, how to make split braids, distorted braids, beaded braids, braids with floats and tufts.

It covers braiding with all kinds of materials—fuzzy, metallic, ribbonesque, small braids incorporated into larger—around a core, with holes, and even shows some variations that include under bobbin movements, rather than the typical over. I have to admit that many of the more esoteric explorations, such as orange ruched ribbon and purple silk braid on p. 5, which looks diseased, leave me cold. However, just seeing all the possibilities, even if they're ones I'd never do, opens up all the many more. Clearly, Carey enjoys both pursuing the traditions and pushing the medium to its limits, and she's to be congratulated.

What it doesn't cover is homemade marudai construction; the traditional names for the braids and equipment; and some of the peruvian and nautical braids in Owen's book. The book's drawings and overall design is attractive—I especially liked the braids running off the side or bottom of the page—but marred by too many typefaces, poor copy editing and occasional out of focus photos—more likely the result of poor production values than the fault of the photographer.

As with Martin's book the photographed samples of the braids are shown many to a page; however, they're referenced only by alpha-numeric labels, rather than names, making it harder (for me, at least) to relate the algorithm to the photographed sample. This sort of thing is a minor detail, but one of my pet peeves. A much bigger problem is that the volume is already out of print, though apparently still available from England; so its price is relatively higher ($29.95) than for the larger, hardbound Owen book, widely available for $24.95. Either volume could be considered an excellent guide for the beginning through intermediate kumist. And if you want to recreate the braid on the Bumble bee necklace? Well, here it is:

YBYB YBBY YBYB YBBY

Arrange your threads clockwise around your braiding stool in this pattern and follow sequence for the 7th braid in Martin's book, Keiruko no himo. (It's 16T, p. 65 in Creative Kumihimo, braid 50, p. 143 in Braids: 250 patterns) To reverse the figure of diamonds and grounds, do half a sequence and then start over (I do this by accident all time).

This is an old page, so it doesn't get the automatic updates the newer ones do...but I rather like it the way it is; however, in the interests of kindness, here are some links to get you back to the less deep dungeoney parts of the site: the main kumi page or, if you came from the Lit direction, the main review page or even back to the top, the main index page. Happy Hunting! (Added 28mar05)

12nov08: Somebody wrote me, from Australia no less, because the pattern as laid out above wasn't working. Ooof. I've known for awhile this wasn't quite right, but the guilt induced by that email finally got me off my butt to fix this page and create the link for more documentation on my most favorite variation of keiruko no himo, ‘twisted diamond’ (or giraffe—it doesn't seem to have an official name) used in the bumblebee necklace. Sorry it took so long!

[1]because the page is so ancient it doesn't support tagging...

[2]Amazon lists it out of print, but it's available from Braider's Hand.

[3]Ooopsie, someone put 1a and 1b again for 2a and 2b.

[4]Yes, they ought always to go together. Alas, it doesn't always happen.

[5]Though I was highly amused by the window reflections in the onyx beads on pp. 66 and 75 (tch, tch, tch), and the image on page 84 is badly underexposed.

[6]I mean theoretically, you could totally scramble the order of the list, but why it make it hard for your readers? Their focus should be on learning your exciting new material, not detangling lists.

[7]Oh, and with new cover photos, slightly rearranged, since the old ones got mangled with the site updating.

Unless otherwise noted, text, image and objects depicted therein copyright 1996--present sylvus tarn.

Sylvus Tarn