I have Annette LeDuff, for whom I did several restringing jobs (of some very beautiful things, including a lovely antique coral hairpin) to thank for what I know of writing up repair jobs of potentially valuable jewelry. The first thing to do is get the customer's name, and address, along with basic instructions (“Restring & retain orig. pattern, due 30 days) and then to describe the piece faithfully as possible:

1 NECKLACE,

- 22K pendant 2” (incl. bail) x 1-1/8” wide

- 17” [long] (not incl. pendant or clasp)

- 6 strands in 2 sets of 3 w/

- 8 5mm round CORR

- 8 4mm gold plastic coat

- 2 3mm ” ”

- 120 2mm ” ”

- brown seed beads

- broken box clasp

Next, I specified what I was to do:

REPLACE:

- all metal beads w/ 14/20 or 14K as appropriate

- clasp w/ 14K fish or lobster, as appropriate

- brown 11/0 seed beads w/ 2mm garnet

- bullion w/ new or metal beads (14/20) as appropriate

- LABOR & MATERIALS NOT TO EXCEED $[amt] TOTAL;

- CUSTOMER NOTIFICATION @>$[smaller_amt]

- (my sig)

I gave a copy of this to the customer, who was a little taken aback at the inventory, and explained to her that she should always expect this level of completeness given the a) value of her materials and b) emotional attachment to the piece. Restring jobs can involve a significant level of trust, and careful invoicing helps establish that level of trust immediately. I also took a digital photo of the piece before I started for reference purposes, another practice I recommend now that it's so easy to do.

The pendant in question is 22K gold, in a traditional Indian design. So is the beadwork, unfortunately, because the stringing materials available in that country are rarely particularly durable. (That is not to say Indian stringers are not skilled. Even in temporarily strung garnets, with sharp holes, they manage to get an amazing number of cotton threads through the beads, often without fraying. Very impressive.)

Though the customer very much wanted to retain the traditional design, she wanted even more to bring the quality of the beads and findings up to match that of the pendant, and particularly to increase the durability of the necklace. She felt the brown beads were ‘lame’, so I suggested garnets, as they a popular bead for traditional Indian jewelry, similar in value and color to the original, and would contrast nicely with the rich gold. She agreed.

22K beads are available in the US, but not readily, and not, as far as I know, in round 2mm; and so I recommended either 14K or 14/20. 14K smooth beads tend to be really fragile, and though I had, years ago, heard of ‘heavy-wall’ 14K beads, my local supplier doesn't carry them (and the clerk didn't know anything about them) and I suspected replacing over 100 2mm beads in them would be prohibitively expensive. So I suggested 14/20, with the possibility of using 14K for the clasp and perhaps the 5mm corrugated. The 4mm plastic coat were actually this intriging smooth bead with a sort of tracery of patterns on top—completely unavailable in 14/20. I thought about getting pave in gold fill, but they were only available in 100pc lots. I don't do much with gold fill anymore, and I balked at the price. I don't remember precisely what alternatives I presented, but the customer chose plain smooth rounds, so that's what I substituted.

Then I actually had to sit down and think about how I was going to restring the piece. The original design was strung in two halves with bullion ends, and with a ring of bullion covered thread connecting them. This was pretty, but not practical. I wanted to restring on 49 stranded beadalon, which is very durable, but requires crimps—no loops. Attempting to run 6 strands of anything through a single coil of bullion is also impractical, but they just barely fit through the crimps I used as a sleeve instead. (I suppose another option would've been to use this new gold-colored beadalon/softflex/whatever, but I'm from the old school, that hides the string, unless to show it off as knots—didn't even occur to me, till I started writing this up.)

I always like to have as few cuts and therefore crimps as possible: the flexing at the crimp is often where stringing materials fail. I knew I would be making my life miserable by cutting only one piece of beadalong and running it back and forth six times, but on the other hand, the customer was paying me handsomely for the most durable job possible, it appealed to my aesthetics and sense of challange...and it meant there would be a messy clump of crimps by the clasp, as there would've been if I'd simply cut six pieces of beadalon, one for each strand.

Tip: any time you're transferring a number of temporarily strung beads, pull a bunch at a time, and string ’em all at once. If one of the beads is poorly drilled, pull off beads to that point, (including the bad bead) opening your finger and thumb enough to drop the bad bead; then transfer. This little trick can save a lot of time.

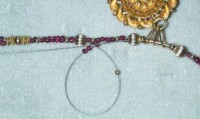

Here I've started the string job, and because I was going back and forth, didn't really have (practically) the option of leaving the beadalon loose until finished, and then pulling it tight. I had to keep the beads snug through out. But, of course, the cable loops like this, and then when pulled tight, kinks. Very annoying.

The way to get around this problem is to insert your finger and guide the beadalon into a hump, which doesn't kink, as opposed to a loop, which does. As the loop draws down, pull your finger out, and guide the beadalon between two fingers, as shown here.

Beadalong now coaxed from a loop, to a hump. Much better. The arrow points to the beadalon currently being strung. The piece on the left is the other end (I started this job more or less in the middle.) Note also the slight change in the design—one garnet instead of two of the brown seed beads between the gold bead accent areas and the 2mm gold fill. This was necessitated by the larger size of the 2mm garnets.

Ramming 6 strands of beadalon through a 5mm bead with ridged holes can be challanging. Twisting (rotating) the bead between the thumb and forefinger while pushing beadalon with the other thumb and forefinger (positioned tightly to the bead in question) can open up enough of a space for the beadalon to squeeze through. Once the tip of it's past the hole, I use my finest chain-nose plier to grab that tiny bit and pull the beadalon the rest of the way. If the tip gets too mashed or frayed, I use my sharpest cutters to trim it, at a diagonal; over the course of stringing, I may repeat this step 5–10 times, cutting perhaps 2–3mm each time. Build this extra into your difficult stringing jobs!

The plan was for the ends to finish on opposite of the clasp. That didn't happen. In fact, not only did both cut ends land on one side of the clasp, I forgot to each insert a crimp on the other! What to do? I finally decided simply, since all that beadalon wouldn't fit in one crimp, to double them up, and then crimp them in such a way they lay flat to each other. Not a perfect solution, but not bad for on-the-fly.

Forgetting to add the crimps was bad enough. Not taking into effect that my findings were shorter was much worse. When the customer got her necklace back, she said, “Uhhmmmm...is it shorter?” I measured, and sure enough, it was. Significantly. I'd made the mistake of matching the length of the beady parts to the original sections, instead of checking to make certain the overall length was the same. I was mortified. I offered to restring (*not* a prospect I was looking forward to). The customer, who had waited substantially more than 30 days for her piece (though to be fair, it took me awhile to round up the replacement components, get her okay, etc.) and I decided she would wear it for awhile, and if it proved unacceptable, I would restring.

Meanwhile, I chalked it to having been out of the game for ten years or so. It's still embarressing, to make such a simple mistake. Note also that the piece lays much more stiffly than originally. This, at least, I did predict. Generally I prefer the stiffer hand of beadalon, and though I was sorry to see the slight loss of the groupings, the piece looked great on the client. She's been happy. My thanks to her, not only for presenting the challange (besides the items mentioned above, there was of course the issue of getting all the strands to come out the same length, with no possibility of adjustment later) but also allowing me to post the job.

Unless otherwise noted, text, image and objects depicted therein copyright 1996--present sylvus tarn.

Sylvus Tarn